A Conversation with Kurahashi Yodo II February 2010

“When samurai lost their jobs they joined komuso temples, but their engagement with the temples was erratic. They would still make themselves available for hire, and therefore often moved on. But, many could never find employment again and remained as komuso monks all their lives, often in a desperate and melancholy state. They did not love their lives and many were rough characters, dangerous and proud. They were not real monks. Degenerate in habits, they often attacked local residents and stole food from farmers.

There were many shakuhachi players during these times, who were NOT komuso monks. Some lords of Northern and Eastern Japan loved to play shakuhachi, as did merchants and lay monks too. Also samurai and common people enjoyed shakuhachi.

The origin of the honkyoku compositions was most likely from the secular players, not necessarily from the komuso temples. For example, Kinko Kurosawa was a samurai, not a monk. It is a huge misunderstanding to say that honkyoku originated in the komuso temples.

Jin Nyodo perhaps reinforced the idea of honkyoku coming out of the temples, because of his touristic tendency to name pieces according to the nearest temple in the area where he received the transmission; temples that had already long since disappeared. It is possible also that Shoganken and Futaiken temples were simply accommodations for traveling komuso, not real temples. Honkyoku pieces were not only given temple names, but also given the name of the person who transmitted the piece. Often therefore, the names of pieces changed in the course of transmission”.

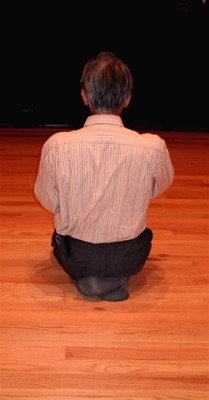

Kurahashi Yodo on Practice

“The idea that practice is not necessary, that we don’t need to be better players and that only spirit is important, is a misunderstanding.

The monks of Pure Land Buddhism talk about the ‘hand of Buddha’. If you practice a piece many times, for many years....perhaps a thousand times, then the hand of Buddha becomes your hand and great beauty can arise in your playing.

Consider a humble, unknown painter, whose daily work is to make the same painting on a ceramic bowl over and over for many years. From such practice one can find ‘real’ art, drawn by Buddha’s hand.

With long practice, perhaps finally the hand of Buddha will play the piece for you.

Great koto and shamisen players, for instance, play perfectly and naturally and with great beauty, and with no ego. They live a simple life. With years of practice, Buddha’s hand enters their playing. This is an ideal of Pure Land Buddhism, not Zen Buddhism.

If you forget Zen, Buddha plays inside you”.

Shakuhachi for sale